Caching in LabVIEW - Strategies, Pitfalls, and Patterns That Actually Work

- Michael Klessens

- Dec 31, 2025

- 13 min read

Intro – Why This Isn’t Just a Sequel

In my last post, The Art of Caching in LabVIEW, we covered why caching matters, when it’s worth the trouble, and the tradeoffs that can make you regret ever touching it. That post was about the decision to cache.

This one is about the execution.

We’re going to dig into concrete caching strategies, the patterns that work well in LabVIEW, and the pitfalls that can quietly turn your “optimization” into a performance-killing, bug-breeding headache.

By the end of this post, you won’t just know if caching makes sense, you’ll know how to implement it to deliver on its promise.

Core Caching Strategies in LabVIEW

Once you’ve decided caching is worth it, the next question is: what’s the smartest way to do it in LabVIEW?

Caching is not a one-size-fits-all solution. The “right” approach depends on your data, your performance goals, and how your application is structured. In LabVIEW, most caching falls into a few broad patterns. Each comes with its own strengths, weaknesses, and ideal use cases.

Note: The code images shown below are intentionally simplified. They are designed to demonstrate the concept, not to serve as the definitive or most optimal approach.

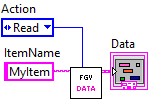

In-Memory Data Structures

For data that needs to be lightning-fast to access, storing it in memory is usually the go-to. This can be as simple as a functional global variable (FGV) or as sophisticated as a LabVIEW class with built-in cache logic.

When to use:

Configuration or lookup tables loaded once and used everywhere.

Data that’s small enough to fit comfortably in memory.

Watch out for:

Memory growth over time.

Needing explicit invalidation when the source changes.

Shift Register / Loop-Based Caching

Sometimes the simplest form of caching is just “keep it in a shift register or feedback node and reuse it until it changes.” This works great for stateful loops, actors, or other components that own their data. The functional global (or action engine) is built on this concept and provides an API for the application to easily access the cached data.

When to use:

Tight, self-contained loops with predictable data lifecycles.

Actor-based designs where other parts of the application can request cached data via messages.

Watch out for:

Without a messaging interface, data is limited to the loop it lives in.

Still requires a plan for invalidation if the underlying source changes.

LabVIEW Maps are a great tool for managing cached data in memory. In legacy versions of LabVIEW, you would need to use Variant Attributes to create maps. Maps are an easier way to quickly lookup your cached data using the maps sorted search algorithm.

Disk-Based Caching

For large datasets or when you need persistence between runs, disk caching is a better choice. This can mean binary files, TDMS, JSON, or even SQLite for structured data.

When to use:

Data too large to store in RAM.

You need the cache to survive an application restart.

Watch out for:

Slower than memory access—use sparingly in time-critical paths.

File format compatibility and versioning issues.

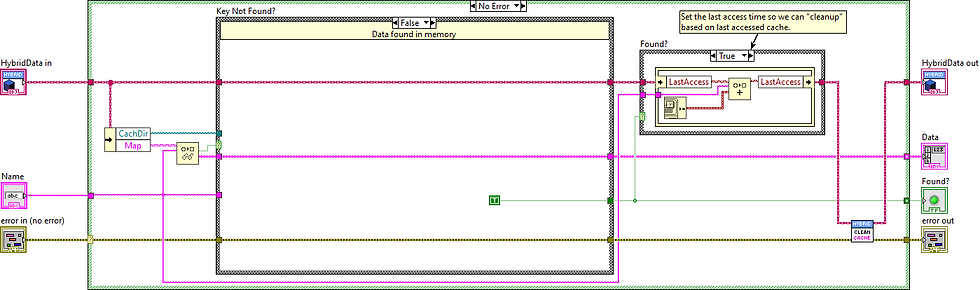

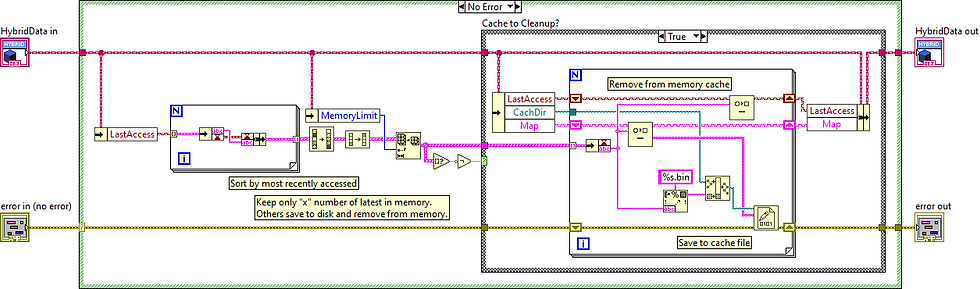

Hybrid Caching

A combination of memory and disk can give you the best of both worlds: keep hot data in RAM for speed, and spill over to disk for persistence or larger storage.

When to use:

Large datasets with a small “working set” accessed frequently.

Applications that must recover quickly after restart without a full reload.

Watch out for:

Added complexity in deciding what lives in memory vs. disk.

Synchronization headaches between the two layers.

The important thing is not to pick the “fanciest” caching method—it’s to pick the simplest one that meets your needs without introducing unnecessary complexity.

Patterns of Caching

When designing a cache, it helps to recognize a few common patterns that guide how data is stored, refreshed, and invalidated. These patterns give structure to your caching approach and can be adapted depending on your test system’s requirements.

1. Read-Through Cache

The application checks the cache first. If the data is missing, it loads it from the source (for example, a database), stores it in the cache, and then returns it. This pattern is simple and ensures fresh data is added on demand.

How it looks in LabVIEW:

The application calls a data retrieval vi that first checks the cache for the data. If it doesn't exist then the same vi reads the cache from disk or database and updates the cache and returns the data. In this case the application doesn't need to worry about the cache, it only is trying to request the data.

2. Write-Through Cache

Whenever data is written to the source, it is also written to the cache. This guarantees the cache is always up to date, though it can add write latency.

How it looks in LabVIEW:

The application calls a data "write" vi which writes the data to memory, but also to the database at the same time. The application doesn't try to manage both, it just calls the one vi that writes to both locations.

3. Write-Behind (Write-Back) Cache

Writes are made to the cache first, and the cache updates the source later in the background. This reduces latency and improves performance in write-heavy systems, but it introduces risk if the cache is lost before the pending writes are flushed to the source.

How it looks in LabVIEW:

Hardware register values are cached in memory as they are written to the DUT. At the same time, a database is used to track changes to those register values. Instead of inserting each change immediately, the application places updates into a queue. A helper loop processes the queue every 10 seconds and performs a bulk insert into the database, reducing overhead and avoiding slowdowns caused by frequent individual inserts.

4. Cache-Aside (Lazy Loading)

The application is responsible for managing what goes into the cache. On a cache miss, the application fetches the data from the source and then adds it to the cache. This provides flexibility and control over caching behavior, such as how long items remain valid or when to refresh them. In contrast to Read-Through caching, the application decides when and what to cache.

How it looks in LabVIEW:

A LabVIEW module or actor manages test configuration data. It can load and cache different parts of the configuration on demand as they are accessed. The same module can also decide when to refresh or reload information back into the cache, giving precise control over performance and data freshness.

In the examples below, the application is deciding to cache only one set of test parameters for a product\model. It knows to do this as many times the same product\model is tested consecutively so it reduces the memory footprint by only loading one at a time. It also handles checking if the test parameters were modified since it was last cached.

5. Time-to-Live (TTL) or Expiration-Based

Cached entries are automatically invalidated after a set time. This is useful when a small amount of data staleness is acceptable or predictable, such as configuration values that rarely change or reference data that can be safely refreshed periodically.

How it looks in LabVIEW:

A LabVIEW module caches calibration constants for a test sequence. Each constant is stored with a timestamp, and the module checks the age of the entry before using it. If the entry is older than the defined TTL, the module reloads the constant from the database and refreshes the cache. This ensures the test always uses reasonably up-to-date values without repeatedly querying the database.

6. Manual Invalidation

The application explicitly clears or refreshes cache entries when it knows the underlying data has changed. This provides precise control but requires careful coordination across the system to avoid stale or inconsistent reads.

How it looks in LabVIEW:

A LabVIEW test system caches parsed configuration files for different DUTs to avoid repeatedly reading them from disk. When a configuration file is modified, the application detects the change and clears the associated cache entry. The next time the DUT is tested, the file is re-parsed and the cache is updated.

By combining these patterns with the earlier strategies (in-memory, disk-based, hybrid, etc.), you can build caches that are not only efficient but also predictable and maintainable.

Common Pitfalls in LabVIEW Caching

Caching can feel like magic when it works. But if you’ve been around LabVIEW long enough, you know that magic tricks go wrong when you miss the details. Here are some of the ways good caches go bad, and how to keep yours out of the dumpster fire.

Stale Data Chaos

If your cache is not refreshed when it should be, you are not improving performance, you are serving bad data faster. That can lead to confusing bugs, wrong test results, or angry users who “fixed” something but still see the old value.

In multi-user systems, stale data can cause leapfrog conditions where one user loads cached data, another updates the same dataset and saves, and then the first user unknowingly overwrites those changes with their outdated copy. Always define exactly when and how the cache is updated, and put safeguards in place to detect changes before writing back.

Over-Caching

Just because you can store it doesn’t mean you should. Dumping huge datasets into memory might look fine in testing, but in the field it can slow your system or even crash it. Be intentional about what you cache and how much memory you’re willing to spend.

Depending on the amount of data you are accessing, caching to disk can also fill up your user's hard drive. If you are using a database, there is no reason to cache the entire database to the users local drive. Using a "last accessed" algorithm like shown in the hybrid approach above can work for caching to disk from DB as well as from disk to memory.

No Invalidation Strategy

A cache without a clear expiration or invalidation plan is a ticking time bomb. Whether it is time-based, event-based, or version-based, make sure there is a clean, predictable way to say “this data is no longer good, get a fresh copy”.

Threading and Concurrency Problems

In multi-loop or actor-based systems, two parts of your code can stomp on each other’s cached values without you noticing, until the results start looking suspicious. If your cache is shared, protect it with proper synchronization or message-passing.

Some methods to keep it protected

Keep the cached data in the responsible actor and use messaging to access it.

Use DVRs so the data is locked when performing a read\modify\write action

Can also use single element queues to lock data access (similar to DVRs)

Use proper APIs around FGV to prevent race conditions during read\modify\write

Silent Performance Loss

Caching has overhead. If you spend more time managing the cache than you save retrieving data, you have lost. Measure before and after to confirm you are actually ahead.

For example, in the hybrid approach example, the "cleanup" was called each time data was accessed. Normally you would not do this, but have some "timeout" or guard-banding. e.g. If the cache limit is 10, you might wait until there are 15 before you perform the cleanup. Or maybe you perform the cleanup check after 1 hour of running the application.

Maintenance Headaches

A cache buried in a tangle of logic becomes a nightmare to update or debug. Keep your caching code clear, documented, and ideally isolated from business logic. You want future-you to thank you, not curse your name.

Real-World Examples and Lessons Learned

Example 1: Win - Speeding Up GUI Responsiveness

A large LabVIEW application had grown into a feature-rich but sluggish tool. Users complained that every button click seemed to hang while the data was fetched.

The root-cause of the lack of responsiveness ended up being the amount of database queries being done to load the data. Instead of loading all the data in one query, it was doing it one data element at a time as that was the "simple" way to do it. It also was making all of the database queries every time it refreshed from one screen to the other. The delay to the user was very noticeable: in some cases, minutes to wait for their data which naturally caused quite a bit of frustration.

Caching Approach Taken:

Reduced the amount of queries and batched them into logical groups. E.g. instead of looping over a query for multiple rows the same type of data, do a single query for all of the rows of data at once.

For the new "batched" queries, made improvements in database schema and indexing that would help speed up the queries.

Added flags in the database tables that indicate when the data has been last modified. Smartest way to do this is using triggers and trigger functions so your application layer doesn't need to worry about setting "data change" events.

Cached the batched "grouped data" to file as well as the meta information about the modified date when the cache was taken.

Since multiple data constructs could be switched between uses, the files for multiple sets of data was kept on disk, but limited (e.g. last 10 accessed data sets kept on disk).

The currently loaded data set was kept in memory even when switching screens (was not the case before). Instead the application would check if the cache in memory was out of date and load only the modified new data.

When changing data sets, the file cache was used and the modified date was also check on load to see if any of the data was out of date and needed refreshed.

As you can see, this solution was fairly involved, but your solution might not need to be. A good approach is to find out at what point your user no longer perceives a delay. A user will not be able to tell the difference between 20ms and 150ms delays as they are working with the GUI. Also, they might not even mind a 2 second delay for that specific operation. In this case, the users were doing the operation so often that small amount of delay were causing frustration, and large delays were causing revolts.

Lessons Learned:

Sometimes caching is less about raw speed and more about user perception. Shaving off even a second or two from repetitive actions can completely change how users feel about your software.

Start with the simplest changes first to see if it meets your users expectations before making the caching algorithm more complex. In this case, start with optimizing and batching database queries before adding in file and in-memory caching.

Example 2: Win - Reducing Database Load in a Test Environment

In a test system lab, every unit under test logged detailed results into a shared database. During peak production hours, dozens of test stations were all trying to insert and query data at the same time. This caused severe slowdowns and sometimes complete system stalls. Engineers were left waiting for results to show up, and operations began to worry about reliability.

Caching Approach Taken:

Introduced a local cache on each test station to temporarily store results.

Instead of writing each result immediately, the system batched writes and committed them to the central database at regular intervals (e.g. every few minutes).

Queries for “last test result” were served directly from the local cache whenever possible.

Added error handling and retries so that if the central database was unavailable, the test station would keep running and flush results once the connection was restored.

Logged both cached and committed results so engineers could still trace failures during debugging.

Lessons Learned:

Caching isn’t only about performance. In this case, the real win was reliability. By buffering writes, the system kept working even when the database was under stress.

Always design a refresh and retry mechanism. A cache without a safety net can lead to data loss, but with the right checks in place it becomes a powerful buffer.

Don’t underestimate the value of batching operations. Even without a sophisticated caching framework, batching alone can drastically reduce load on shared resources.

Side Note: There are ways to batch DB queries (multiple rows in one query) even if you have a mix of unknown insert/update values, commonly referred to as upserts. So do not think you need to separate your queries because of this situation. Huge gains can be attained by utilizing these methods.

Example 3: Pitfall - Stale Cache in Long-Running Test Sequences

A LabVIEW test sequence cached product-specific parameters from the database at startup. These parameters were later updated in the DB mid-run by other systems, but the cached copy in the test sequence never refreshed.

Consequence:

Test logic used outdated values, leading to inaccurate results.

Debugging was painful — logs pointed to correct DB entries, but the test logic still relied on stale cache.

What Went Wrong:

The caching strategy didn’t account for data that could change mid-execution.

Lesson Learned:

Always define cache invalidation rules. Ask: “When is this data no longer safe to reuse?”

For dynamic data, consider shorter cache lifetimes or explicit refresh mechanisms.

Side Note: "Normally" for device tests you would only update test parameters at the start of the test, but when starting the next DUT you would check to see if the cache is still valid. This isn't a hard fast rule, just what is normally done for shorter test executions. I have seen mid-testing updates for long test executions though.

Bringing It All Together

Caching in LabVIEW isn’t just about shaving a few milliseconds off execution time, it’s about improving the entire user and developer experience. By reducing redundant work, smoothing out responsiveness, and lowering system load, caching helps your applications feel faster, more reliable, and more professional.

The examples we walked through highlight a key point: effective caching is as much about design choices as it is about performance. Whether it’s cutting down on expensive DB queries, avoiding repeated calculations, or keeping interfaces snappy, the right caching strategy can change how both engineers and end users experience your system.

Of course, what we’ve covered here is only the starting point. The real challenge comes when you need to balance freshness with performance, decide when cached data should expire, or scale caching across distributed systems. Those tradeoffs: invalidation strategies, eviction policies, and advanced patterns, are what we’ll dig into next.

Caching may look simple on the surface, but done thoughtfully, it becomes a cornerstone of building LabVIEW applications that are not only fast, but also elegant and resilient.

Comments